I’ve known of Rod Carley’s work for over twenty-five years. In February 1987, I had seen his performance as Algernon in Whitby Courthouse Theatre’s production of ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’. Whitby had also obtained a grant to hire Rod as the director of their Youth Group production ‘The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe’. The Oshawa Little Theatre had also hired Rod to direct its production of a good production of ‘Dancing at Lughnasa’.

Rod is an award-winning director, playwright and actor from North Bay, Ontario, having directed and produced over 100 theatrical productions to date including fifteen adaptations of Shakespeare. Rod is the Artistic Director of the Acting for Stage and Screen Program for Canadore College and a part-time English professor with Nipissing University. He was the 2009 winner of TVO’s Big Ideas/Best Lecturer competition.

His first novel, A Matter of Will, was a finalist for the 2018 Northern Lit Awards for Fiction. His short story, ‘A Farewell to Stream’ was featured in the non-fiction anthology, 150 Years Up North and More. I’ve just finished his second novel Kinmount and will post a review at the conclusion of Rod’s profile.

Thanks to Nora McLellan who encouraged me to read Rod’s book and to Rod for writing it and for taking a few moments to chat with me about the state of the arts going forward from a Covid to a post Covid world:

In a couple of months, we will be coming up on one year where the doors of live theatre have been shuttered. How have you been faring during this time? Your immediate family?

Health wise, I’m okay. I had to cancel two directing projects and an acting project as well as my fall reading tour for my new novel KINMOUNT.

My immediate family is in good health.

Fortunately, I’m based in North Bay, ON. This region has a small number of active cases.

Teaching, Netflix, (not to be confused with teaching Netflix), family, the arts, books, the cats, Zoom chats with friends, doom scrolling, my writing, and connecting with the theatre and writing community on social media have been helping me get through COVID. Together although alone. When one of us is having a hard day, the rest jump in with words of encouragement and hope. “No one gets left behind,” is our unofficial motto.

After ten months in, everyone is weary from daily COVID battle fatigue and uncertainty of the future.

Each day feels like trying to herd a different cat.

How have you been spending your time since the theatre industry has been locked up tight as a drum?

As well as an author and free-lance director, I am the Artistic Director for the Acting for Stage and Screen Program at Canadore College – a training program I created in 2004 due to the lack of actor training north of Toronto. Because of the small number of COVID cases in this region, we have been able to keep 70% of our acting classes in the classroom, practising physical distancing and wearing masks. We are one of the few actor-training programs in the province that hasn’t had to switch entirely to on-line delivery.

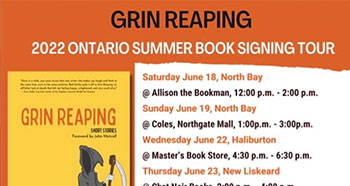

I’ve been doing a lot of writing. My new novel KINMOUNT was published this past October. Launching a new book smack dab in the middle of a pandemic is not for the faint of literary heart. Using the new COVID lingo, I “pivoted” and did a virtual launch (one positive was the number of friends who were able to attend from across the country and internationally). My publisher and I have relied heavily on social media to market the book. I’m also in the final editing stage of a new collection of interconnected short stories entitled Grin Reaping.

I’ve done quite a few Zoom readings at online literary events.

Last April, I retaught myself to play the accordion and posted regularly on social media to put a little light and humour into people’s days…or drive them further over the edge.

The family tabby cat, Hilton, amuses me to no end. Our other older cat, Zoe, passed away in September. Last summer, I created a series of social media posts featuring Hilton and Zoe called “Respect for Mewing,” a purrfect parody on Uta Hagen’s “Respect for Acting.” Their antics might even lead to a book.

I’ve also watched some very resourceful theatre companies move their programming online. Tarragon Theatre’s staged reading of David Young’s Inexpressible Island at the start of the pandemic was particularly well done – the six actors speaking out of the darkness in their respective spaces captured the isolation of the piece. I’m looking forward to watching Rick Roberts’ online mythic adventure Orestes, directed by Richard Rose, this coming February.

Still, nothing can replace live theatre. There is a sanctity to what we do as theatre artists. People gather together to experience things that can’t otherwise be experienced – not unlike what happens in a church or synagogue. There’s an elevation, a nobility, and a feeling of sanctuary.

Arthur Miller said, “My feeling is that people in a group, en masse, watching something, react differently, and perhaps more profoundly than they do in their living rooms.”

The late Hal Prince described the theatre as an escape for him. Would you say that Covid has been an escape for you or would you describe this near year long absence from the theatre as something else?

COVID is a restriction rather than an escape. In the theatre, flight-within-restriction is the director’s goal. A director has to know all the resources and limitations they are working with. Only then can they know in which direction freedom lies. Ironically, for me, it’s become a working metaphor for coping during COVID.

I’ve interviewed a few artists several months ago who said that the theatre industry will probably be shut down and not go full head on until at least 2022. There may be pockets of outdoor theatre where safety protocols are in place. What are your comments about this? Do you think you and your colleagues/fellow artists will not return until 2022?

Dr. Fauci was recently quoted in The New York Times as saying he believed that theatres could be safe to open some time in the fall of 2021 – as long as 70% to 85% of Americans were vaccinated by then. Will those percentages apply to Canadian theatres?

The quality of a theatre’s ventilation system and the use of proper air filters will play a vital role. Theatregoers may need to continue wearing masks. Strict hygiene protocols will need to be in place.

Reduced capacity of seating has been another roadblock in the financial viability of reopening. Fauci believes theatres will start getting back to almost full capacity of seating. Another possibility is to ask audience members to show proof of a negative virus test –as required by some airlines.

I am currently directing an online college production of David Ives’ All in the Timing, scheduled to go up in April 2021. I hope my colleagues and I will be able to direct live productions by the spring of 2022. Even with the vaccine, however, we will have to see if audiences feel comfortable returning to the theatre. Post-COVID, it may take awhile until they feel fully safe.

I had a discussion recently with an Equity actor who said that yes theatre should not only entertain but, more importantly, it should transform both the actor and the audience. How has Covid transformed you in your understanding of the theatre and where it is headed in a post Covid world?

A quote from my new novel KINMOUNT:

“For nearly four thousand years, theatre had survived religious persecution, war, plague, the rise of television, AIDS, CATS, funding cuts, and electronic media.”

(KINMOUNT – Part Two: Madness, Chapter 8, p. 173)

But can the theatre survive COVID?

My response is, “Yes.”

We’ve probably all heard somebody say that come the End of the World, the only survivors will be the cockroaches. Cockroaches have been around for over 300 million years – so they’ve outlasted the dinosaurs by about 150 million years…and they are tough little creatures. They can survive on cellulose and, in a pinch, each other, and they can even soldier on without a head for a week or two – and they’re fiendishly fast as well as many of us have discovered opening an apartment door and turning on a light. They have the reputation for being survivors – living through anything from steaming hot water to nuclear holocaust….and, when they do survive Armageddon, they will probably be performing theatre!

There is something of the scrappy cockroach in every actor. Theatre has survived a variety of “end of the world” scenarios since its earliest beginnings. From the stone ages, men and women have been telling stories by enacting them even when no language existed. Ancient Greek theatre still inspires us, and it continues to be staged in all the languages of the world. In Ancient Greece, we had an empire ensconced in domestic barbarism and military adventurism. Yet, it was the theatre that reformulated the debates of that era with humanity and intelligence and put those qualities back in the air we still breathe more than 2,000 years later – and theatre will do that again post-COVID.

Starting in the Dark Ages, actors were forbidden the sacraments of the church unless they foreswore their profession, a decree not rescinded in many places until the 18th century. Can you imagine the great French playwright Moliere collapsing on stage to his death and being denied the last rights? King Louis the 14th had to intervene to grant Moliere a Christian burial. Actors were treated as heretics for nearly 1,300 years! They know about tenacity and survival.

During the 1950’s the world lived under the threat of an atomic war capable of ending life on earth. It was an age of anxiety and stress. The theatre was heavily influenced by the horrors of World War II and the threats of impending disaster. Serious questions were raised about man’s capacity to act responsibly or even to survive. Anxiety and guilt became major themes. Probably more than any other writer, Samuel Beckett expressed the postwar doubts about man’s capacity to understand and control his world. Now, “the end of the world” really was around the corner but it didn’t stop theatre. The cockroach artists kept holding that cracked and broken mirror up to man’s doubtful nature.

We may see post-COVID theatre addressing similar issues – the fall of the American Empire, climate change, reconciliation, and so many other pressing societal ills – coupled with a need for humour and escape.

I think there might there be a backlash coming against digital technology. The human soul is screaming for meaning. How much spiritual hunger and alienation can we bear?

Theatre is genuine communication and not short form twitters and tweets. An audience is alive in the same space where the actors testify the truth of their characters. Any place where you are in that kind of public forum, breathing the same air, the truth will come out.

The late Zoe Caldwell spoke about how actors should feel danger in the work. It’s a solid and swell thing to have if the actor/artist and the audience both feel it. Would you agree with Ms. Caldwell? Have you ever felt danger during this time of Covid and do you believe it will somehow influence your work when you return to the theatre?

We live in a dangerous era now where the arts are being seriously questioned. In an uncertain economy, the arts are often among the first things to be eliminated from discretionary spending.

The fall of the American Empire is rife with danger. The rise of right-wing fascism is beyond scary.

In many articles, the pandemic has been compared to Shakespeare and the plague.

In this excerpt from my novel, KINMOUNT, down-and-out-director Dave Middleton talks to his acting company at the First Reading of his production of Romeo and Juliet:

“Romeo and Juliet was the first play to be produced in London after the infamous Black Death of 1592 to 1594 wiped out close to a third of the population,” Dave explained. “All the theatres were shut down for three years. Images and references to the plague permeate the play such that the plague itself becomes a character—much the way Caesar’s ghost haunts and dominates Julius Caesar. The plague struck and killed people with terrible speed. Usually by the fourth day you were dead. The time frame of Romeo and Juliet moves with a similar deadly speed, from the lovers’ first meeting to their deaths.”

“I can’t imagine waking up on Saturday and being dead by Tuesday,” said Miranda.

“The plague underscores all that happens, mirroring the fear and desperation of the characters’ individual worlds,” said Dave, adopting a sombre tone. “I’m pretty sure most of us have lost someone to cancer.” The company nodded uncomfortably. “We can only imagine the dreadful immediacy of Romeo and Juliet when it was first performed for an audience who had each lost family and friends to the plague. Here was a play referencing that very loss and terror.” Dave circled his troops; his director’s passion, despite himself, as infectious as the plague he was referencing. “What a gutsy and attention-getting backdrop for the love story that unfolds in the wake of Ebola, the opioid epidemic, Lyme disease, HIV, not to mention the scourge of cancer, we know what this fear is like.” Dave had hit a nerve.

“By using the original setting and its plague components,” Dave explained, “our production will serve as an analogy for today. We will play the humour of the first three acts to its fullest until the “plague” of deaths begins. We will explore the passion and exuberance of youth, the need to live every day as if it was your last, because it very well could be. Your life expectancy is thirty.”

“Whoa,” said the taller stoner. “Like I’m already middle-aged. That sucks, dude.”

“It does,” said Dave. “You have no idea what will happen when you start your day. You could be killed in a duel, run over by horse-drawn cart, be accidentally hit on the head by a falling chamber pot, or drink water from an outdoor fountain, toxic with bacteria boiling in the summer heat, and catch the plague.”

(KINMOUNT– Part One: Meeting, Chapter 7, pp. 48-49)

Similar to the plague, COVID has reinforced the transience and fragility of our existence. We really do have to embrace the moment because the future is more uncertain than ever. Post-COVID, this reality will serve as a backdrop for much of the theatre that will be created, whether consciously or unconsciously.

The late scenic designer Ming Cho Lee spoke about great art opening doors and making us feel more sensitive. Has this time of Covid made you sensitive to our world and has it made some impact on your life in such a way that you will bring this back with you to the theatre?

As a theatre artist, I’ve always been sensitive to the world – it’s in my DNA. Theatre has a responsibility to society – to educate, enlighten, and, hopefully, change. Theatre has been doing that for centuries. The theatre has always been, at least for me, about rekindling the soul and discovering what makes each of us human – it is the touchstone to our humanity. It is the most immediate way in which a human being can share with another the sense of what it is to be a human being. It speaks to something within each of us that is fleeting and intangible. And we feel less alone. Given our present circumstances, we need this more than over.

The power of stage is enormous because it is real. We all live in what is, but we find a thousand ways not to face it. Great theatre strengthens our faculty to face it. Theatre provides for the psychic well-being and sanity of a society. We will need it more than ever post-COVID.

In Shakespeare’s day, great plays were thought of as mirrors. When you see a play, you are looking into a mirror – a pretty special mirror, one that reflects the world in a way that allows us to see its true nature. We also see that it not only reflects the world around us, but also ourselves. This two-way mirroring means that learning about great theatre and learning about life go hand in hand. And it means that finding beauty and meaning in great theatre is a sort of proving ground for finding beauty and meaning in life.

Again, the late Hal Prince spoke of the fact that theatre should trigger curiosity in the actor/artist and the audience. Has Covid sparked any interest in you about something during this time? Has this time away from the theatre sparked further curiosity for you when you return to this art form?

The need to tell stories of what it is to be human remains crucial to me – stories about who we are, why we are, where we came from, and what we may become – with curiosity and hope. Stories that challenge the right-wing capitalist patriarchal hegemony.

I will continue to revisit relevant older works with a fresh lens, making them accessible to today’s audience. I am committed to developing new works by Northern Ontario voices.

For years, I have been working on an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar based on Pierre Elliot Trudeau, the FLQ and events surrounding the October Crisis of the 1970. In my interpretation, Caesar is, of course, based on Trudeau and, in the transported setting, he is assassinated in Ottawa by members of the FLQ as an act of revenge in the wake of his handling of “Black October.” The adaptation would involve both official languages and would employ colour conscious casting. It might never to see the light of day.

I am also looking into creating podcasts for my new short story collection.

I am in the early outlining stages of a new novel that will be a comic tale of writer’s block, the chopping block, ghosts, and ghostwriters.

Joe’s review of Kinmount:

KINMOUNT REMINDS US OF THE IMPORTANCE OF AND FOR THE ARTS NOW MORE THAN EVER

While reading Rod Carley’s Kinmount, I couldn’t help but make a comparison of it to Miguel Cervantes’ Don Quixote for the literary term I remember from my second year undergraduate course at the University of Western Ontario – picaresque. I loved the sound of that word then and It still like the sound of it today.

Just to review this term – A picaresque hero is a charming fellow who battles sometimes humorous or satiric moments and episodes that often depict in real life the daily life of the common person. Much like Don Quixote’s fight with windmills, Carley’s protagonist (Dave Middleton) is a professional theatre director who has been hired by oddly eccentric producer Lola White to direct a community theatre production of Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet in Kinmount, Ontario. Dave ends up battling with oddball characters, censorship issues, stifling summer weather and shortage of monetary funds in his quest to ensure the production is staged the way he believes Shakespeare had wanted it to be staged.

I reluctantly admit I had no clue where the town was as I’ve no reason to attend so I had to look it up on a map.

Okay, once I saw where it was located, I will also be honest and state I didn’t know if I even wanted to visit the town as Middleton describes it as “Canada’s capital of unwed mothers under the age of twenty…kids having kids. And the rest are grammatically challenged and wear spandex. And that’s just the men.” I do sincerely hope Middleton’s description of the real town is tongue in cheek.

Thankfully Carley tells us at the end of his book that he “chose the name simply because of the comic noun and verb combination. For no other reason” as “The real-life Kinmount is a lovely spot nestled in the beautiful Ontario Highlands and home to a population of five hundred friendly highlanders and summer cottagers.”

Since I am a theatre and Shakespearean lover of language Kinmount, for me, became a touchstone of the crucial importance the arts provide us especially now in this time of shutdown, lockdown, and a provincial stay at home order of the worldwide pandemic.

If we have been involved in community theatre productions, Kinmount becomes a hilarious remembrance of those moments when we all stoically wondered if the show would ever come together given the ‘behind the scenes’ world of egos, divas and divos, and oddballs just to name a few. Carley’s style never becomes pedantic but instead a playful reminder of those who select to participate in theatre, whether professional or community, just why we keep returning to this dramatic format. It is for the love of the spoken word.

Rod and I spoke briefly via FaceTime about the ending of Kinmount and how touched I was at the final actions of protagonist Dave Middleton. Given the veritable struggles Dave must endure throughout the story, sometimes comical, sometimes frightening, he reveals a compassionate, human side that we must all never forget that we too can be like Dave in stressful times.

It’s worth a visit to Kinmount.

Kinmount now available at Latitude 46 Publishing (www.latitude46publishing.com), Indigo, Amazon and your favourite bookseller. I picked mine up at Blue Heron Books in Uxbridge, Ontario.

Artricle by: Joe Szekeres – www.onstageblog.com